Secure your ticket for the Global Fashion Summit: Copenhagen Edition 2024!

Accelerating impact

to create a net positive fashion industry

Accelerating impact

to create a net positive fashion industry

Global Fashion Agenda is a non-profit organisation that fosters industry collaboration on sustainability in fashion to accelerate impact. With the vision of a net positive fashion industry, it drives action by mobilising, inspiring, influencing and educating all stakeholders.

Secure your ticket for the Global Fashion Summit: Copenhagen Edition 2024!

A net positive industry for people and the planet is an industry that puts back more into society, the environment, and the global economy than it takes out.

The organisation has been leading the movement since 2009 and presents the renowned international forum on sustainability in fashion, Global Fashion Summit, in core industry regions around the world. GFA influences policy through its advocacy efforts including the Global Textiles Policy Forum, publishes thought leadership including The GFA Monitor, Fashion CEO Agenda and Fashion on Climate, implements impact programmes including the Circular Fashion Partnership and the Global Circular Fashion Forum, presents educational guidance through the GFA Academy, and connects companies with solutions through the Innovation Forum.

of microplastic pollution in the oceans

come from micro fibres shed by synthetic fibres

Read more - Fashion CEO Agenda

The fashion industry is one of the largest, most resource intensive industries. It is a powerful engine for global growth and development.

The apparel and footwear industry accounted for some 2.1 billion tonnes of CO2 emissions in 2018, about 4% of the global total. For context, this is the same quantity of CO2 per year as the economies of France, Germany, and the United Kingdom combined. The global apparel market is projected to grow in value from 1.5 trillion USD in 2020 to about 2.25 trillion USD dollars by 2025, and it employs 60+ million people along its value chain; of which 80% are women. Widespread negative social implications within its supply chain such as the challenges in human rights, raising social standards and eliminating forced labour are all too familiar issues.

With global garment production to increase by 63% by 2030 – the equivalent of 500 billion shirts – the current business model of the fashion industry is unsustainable and needs to change to align with the Sustainable Development Goals.

We can form a thriving industry that creates prosperity for people and communities, reverses climate change and protects biodiversity. For this to happen, action is required now.

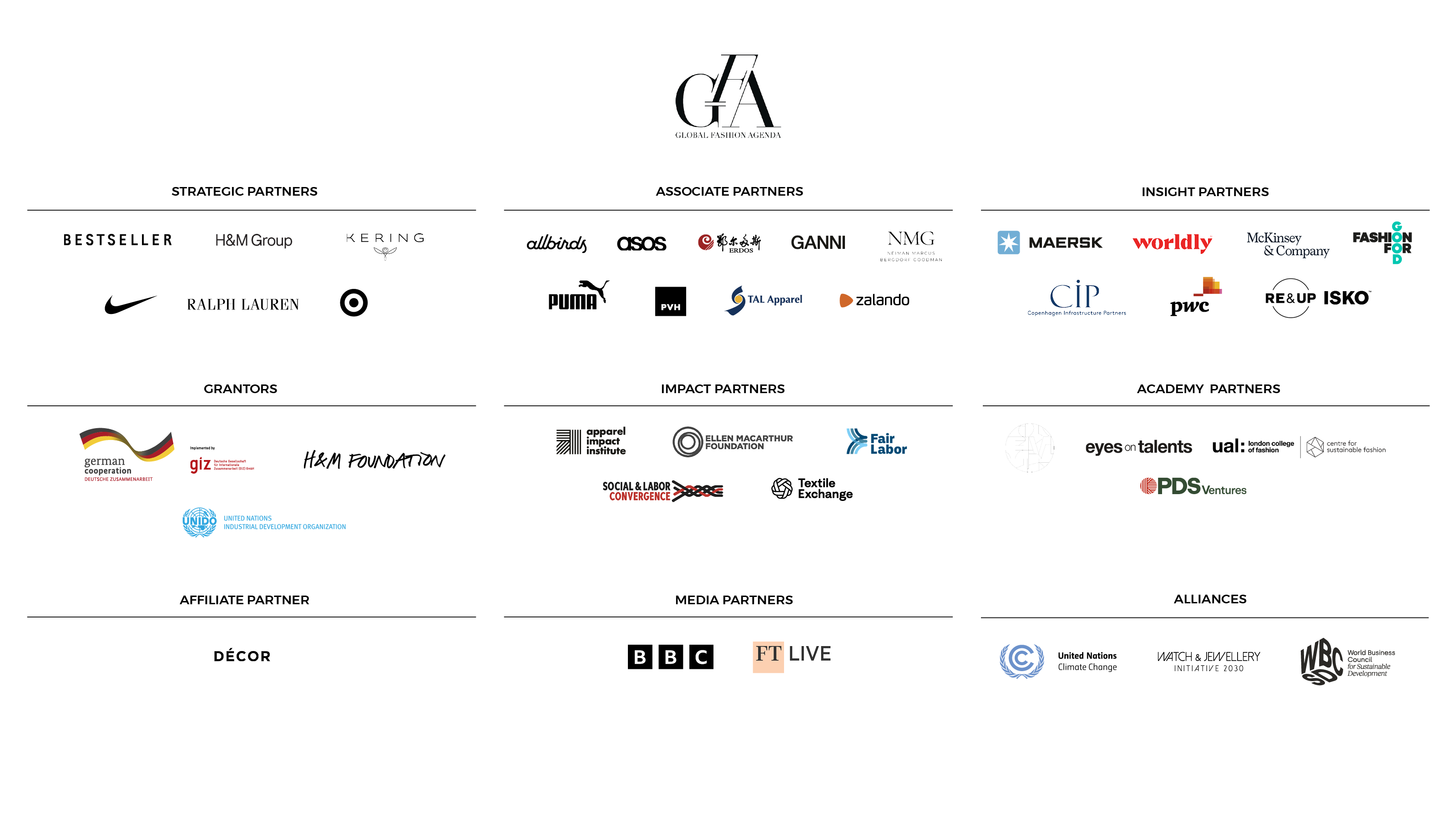

Working in partnership with a wide ecosystem of companies and organisations across the value chain, GFA spearheads the fashion industry’s journey towards a more sustainable future. Through its work, GFA reaches thousands of stakeholders including brands, innovators, NGOs, policy makers, manufacturers, investors and more.

GHG reduction by 2030 & Net zero GHG emissions by 2050

workers earn a living wage

the use of virgin polyester, conventional cotton & conventional manmade cellulosics. Significantly reduce the use of finite resources.

Download your copy of The GFA Monitor Report 2023